ALAN’S EXPERIENCE WITH HOMELESSNESS

In 1995, Alan Banks held a top-secret security clearance and was making six figures. By 2004, he was living on the street.

“You can have a lot materially and homelessness can still get you,” Banks said, “Homelessness can happen to anyone. It can happen to you.”

Banks was 45 when he experienced homelessness for the first time; he faced it twice over the course of six years. In 2010, Friendship Place, a housing service provider for those experiencing homelessness, helped him find housing and rebuild his life. Today, he works as a Community Engagement Associate for Friendship Place, where he uses his story to educate people about homelessness. He has even acted as a mentor.

Russell Williams experienced homelessness for three years without even realizing it. Instead of living on the street, he slept in hotels, at friends’ houses, or in his car. Banks helped him acknowledge that he was homeless and introduced him to Friendship Place, which provided stable housing for him.

“He actually kind of talked me into accepting the help,” Williams said. “He’s a very good friend.”

Williams describes Banks as a kind, passionate person who is determined to help others succeed the way he did.

There are around 5,111 people experiencing homelessness on any given night in the D.C., according to The Community Partnership’s 2021 Point-in-Time Count,. Within that group, 66% are male, 32% are female and the remaining 2% identify as gender-nonconforming or transgender. The vast majority of those experiencing homelessness, about 86%, are Black. Almost half have been diagnosed with a chronic health or mental health condition.

Banks’ experience with homelessness was caused by mental illness. Severe depression and extreme introversion had a detrimental effect on his life.

During the first half of his career, Banks was able to manage his symptoms well enough to function. As someone who held a top-secret security clearance, Banks used his introversion to his advantage by keeping friends and coworkers at a distance. When he felt that his mental health started affecting his work, he would simply go elsewhere.

“When things got bad, instead of fixing the issue I would just leave, and because of my clearance, I could go anywhere and get a job,” Banks said.

At home, things were different. His introversion made it difficult for him to connect with his family. Instead of spending time with his wife and kids when he got home from work, he would collapse into himself. His wife exerted a considerable amount of energy trying to fix his mental health, but it never worked. Over time, the weight became too much for her and the two got divorced after nearly twenty years of marriage.

Depressed and facing divorce, Banks began to outspend his income on items like jewelry, TVs, stereos, and more instead of paying his bills.

“I spent a bunch of money. I bought things I put in the garage and never touched again,” Banks explained. “It felt good to go buy something.”

Everything changed in 1996 when his father unexpectedly passed away. Banks found himself in a deep, crippling depression that he’d never felt before. It began to seep into his work performance. He would arrive to work late or called out sick consistently. It got to a point where he lost his job, and within two years he was homeless.

Banks’ first few months of homelessness were unbearable. He completely isolated himself; when he saw someone walking toward him, he would quickly go in the opposite direction. As a result, he couldn’t utilize the social services that were available to him because he didn’t know they existed.

“I didn’t take a shower for over three months,” Banks said. “I had no concept in my mind that there was somewhere someone experiencing homelessness could go take a shower.”

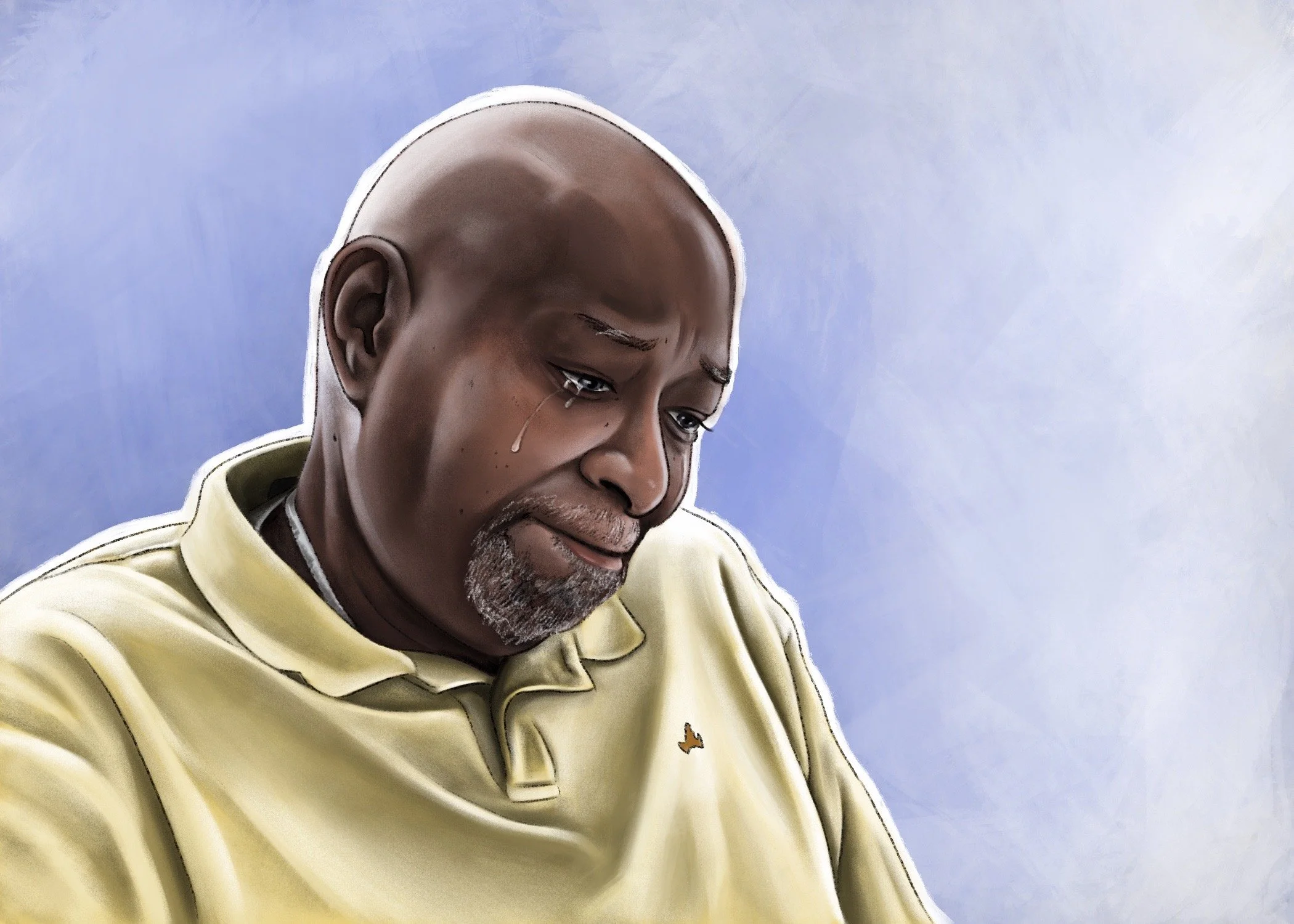

As he reflected on his experience, Banks became emotional. He would take long pauses to stop himself from crying. He choked up as he explained that he didn’t speak a word for three months, forgetting the sound of his own voice. Tears slipped down his face as he recalled the first time he ate out of the trash.

Today, Banks acknowledges that there were programs in place that could have prevented him from becoming homeless. But at the time, the idea of asking for help was something he couldn’t fathom.

“I never asked anyone for help in my life ever,” Banks said, “So I lost it all.”

After three years on the street, Banks began living in a large shelter. The conditions of the shelter, its filth, overcrowding, and lack of personal space, made for a miserable experience.

“Shelters can be one of the worst places in the world,” Banks said.

Banks managed to get himself out of the shelter and into a small apartment. Determined to do everything right, Banks started going to work and paying his bills.

On December 4, 2006, Banks left his apartment to head to work only to find someone waiting to rob him in the hallway. The situation escalated quickly, and Banks was shot three times, his left hand taking on the most damage. Unable to work, Banks landed right back into the shelter.

With his body broken and his mental health shattered, Banks began to plan his death. As he started to lay out a plan in his head, Banks became frightened. The idea of suicide, which was previously unthinkable, shook him.

“That drove me to do something that was totally foreign for me,” Banks said. “Which was to ask for help.”

Asking for help was the key Banks needed to climb out of his experience with homelessness. He was put in touch with Friendship Place, which found him an apartment within a week.

“But that’s just the first step,” Banks explained. “If you don’t take the other steps the first step falls apart.”

Friendship Place connected Banks with counselors and psychiatrists who could help him successfully manage his mental health. They also provided him with a case manager and a mentor, both of whom he spoke with on a weekly basis.

His mentor, Bryan Smith, helped him relearn the things he forgot how to do while he was experiencing homelessness, like budget his money, grocery shop, and enjoy an evening out. Over time, Smith became one of Banks’ dearest friends.

“I think that resiliency is one of the most impressive things that I’ve learned from Alan,” Smith said, “and the human spirit’s ability to climb back.”

Housed, working, and managing his mental health, Banks found a way to reunite with his family. Banks went from thinking he would never see his children again to celebrating important milestones with them, like his son’s wedding and his daughter’s graduation from nursing school.

Banks’ life had drastically changed over the course of ten years. Sitting on a park bench before seeing a movie with a friend, he realized something special.

“When I get up from this bench, I get to go home,” Banks said, as another tear fell from his eye. “It’s not much but it can be everything.”